You know you’ve made it when BBC marketing includes your name in the title of a book, let alone a TV series. The Power of Art might seem a catchy title in its own right, but by assigning the ownership of the concept to Simon Schama, the publisher is admitting that the cult of personality is a greater lure for readers than art itself. Or perhaps it’s just the magnitude of personality involved. After all, the book deals with eight obscure historical figures: Caravaggio, Bernini, Rembrandt, David, Turner, Van Gogh, Picasso and Rothko – nobody quite so famous as Simon Schama.

By now Schama has been involved in so many TV tie-ins that he is probably quite indifferent to anything a marketing department can dream up. He may feel it is a small price to pay for the opportunity to reach such huge audiences and dazzle them with his erudition.

Power of Art feels as if it has been written in one breathless burst of enthusiasm, in a prose style that crackles like electricity. Schama sets out to investigate the creation of eight great works of art via a rapid jaunt through the biographies of eight great artists and the stages that led up to that eureka moment. “When they happened, in a bolt of illumination,” he writes, “the works tell us something about how the world is, how it is to be inside our skins, that no more prosaic source of wisdom can deliver.”

So the stakes are high – Schama wants us to understand how a work of art may change one’s life, how it can make us see the world as we have never seen it before. He also wants us to realise how visionary these artists were, for their careers are punctuated by spectacular failures. Those failures were sometimes the fault of an uncomprehending, hidebound audience, but were often due to the difficulties of artistic temperament.

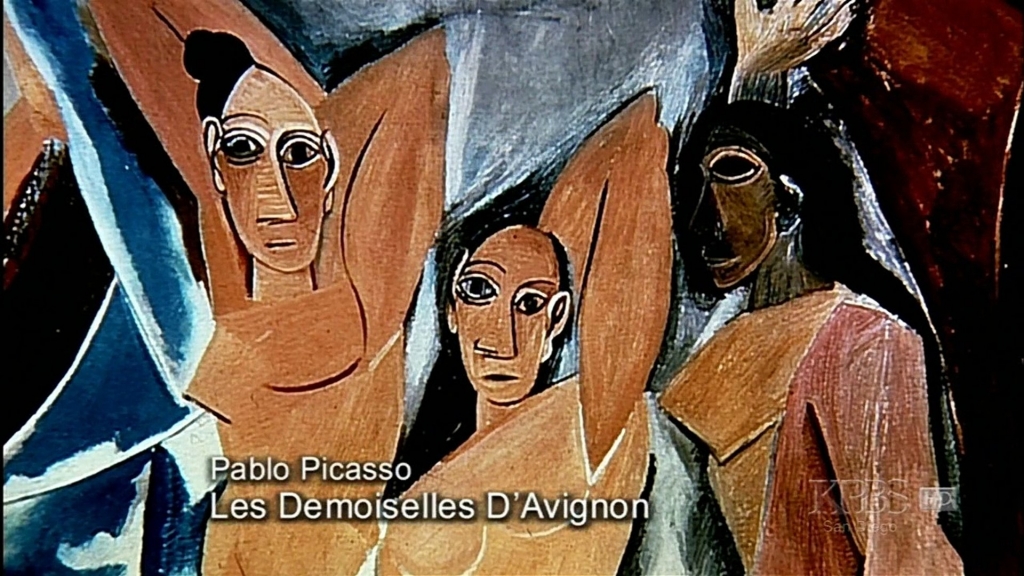

Imagine a dinner in heaven, or the other place, with Caravaggio, Bernini, Rembrandt, Turner, or any of the masters featured in this book. It would be an unbearable clash of egos and intensities. Take David, the apologist for terror, and Van Gogh, the needy evangelist; Picasso, the mischievous extrovert, and Rothko, obsessive and depressed.

Schama knows one cannot read a work of art as the direct product of an artist’s personality or biography but he allows us to draw all the necessary inferences. The next inference – one has to be a deeply flawed human being to be able to create a masterpiece for all time – is left as an open question.

While he knows words can never duplicate the mysterious force of a great painting, Schama does his best to describe his own passions when confronted by a work such as Caravaggio’s The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist or David’s Marat. At times it feels as though he is reaching out of the book to grab the reader by the collar. Some of his phrases are miraculously apt, others over-the-top. Rembrandt, when he wanted, “could paint like a fashion shoot”, although his nudes were “symphonies of cellulite”. In Van Gogh’s Night Cafe in Arles (1888), “the colours barge into each other like drunks looking for a fight”. And so on, until the profusion of similes and metaphors begins to feel slightly indigestible.

Schama is in love with his own eloquence and wants us to be equally smitten. If it is only human to resist that kind of appeal, it is also difficult to deny his brilliance.

The success of his method depends on an almost cinematic form of narrative. Like a Hollywood director, he has the ability to turn the most humdrum aspects of an artist’s biography into high adventure. Like Hollywood, he likes to view the past through the lens of contemporary preoccupations. Rembrandt, for instance, is compared with an “eBay addict” in his compulsive collecting of antiques and curios.

Schama composes his vivid portraits in defiance of all the hesitations and footnotes one finds in more conventional art history. While most art historians will warn the reader an anecdote is only hearsay or exists in disputed versions, Schama will bring us the best, most engaging version in the guise of a fact. This is one of the reasons he irritates academics, although they are probably more irked by the popular success of his books and films.

But no matter whether one adores or loathes his style, one has to admit Schama is on the side of the angels. To encourage us to forsake the audio-tour for a minute and leave ourselves open to the sheer staggering power of a work of art is a noble mission. Too often we are in a hurry to tick another museum or masterpiece off our list and race on to the next. Yet a truly great painting makes time stand still, makes us oblivious to our surroundings and conscious of the ineluctable affinities that bind the past to the present.