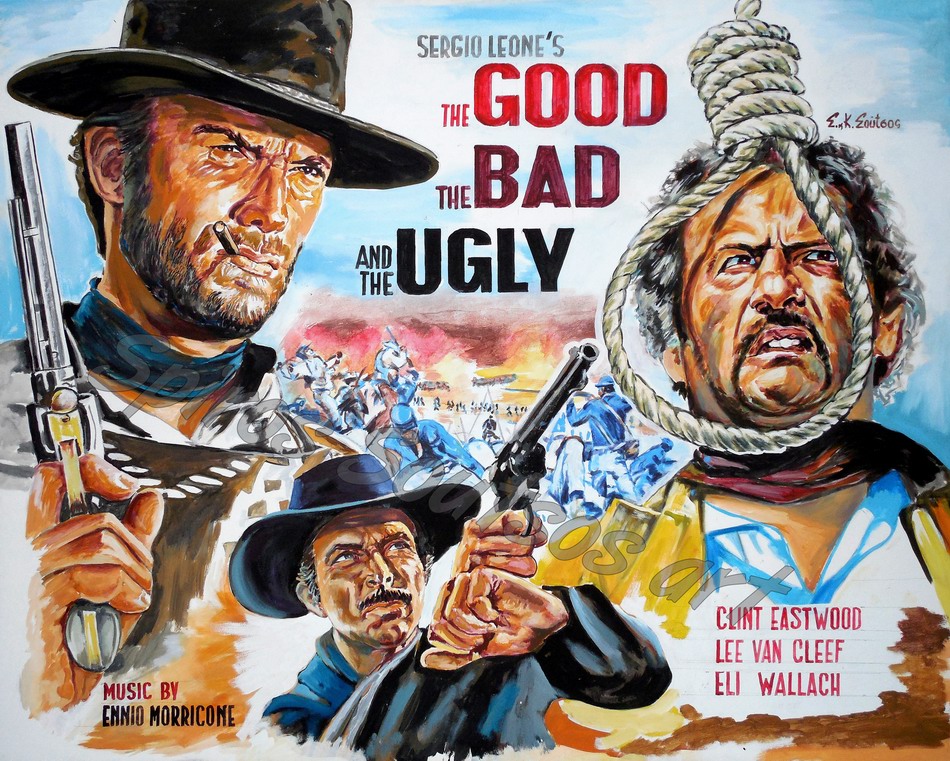

Now we have come to the last, and undeniably the best, of Sergio Leone’s “Dollars Trilogy,” “The Good, the bad and the Ugly,” released in 1966.

Eric Henderson started his review out by saying, “It seems inconceivable now that spaghetti westerns, specifically those served up by Sergio Leone, were once considered to be somehow less faithful to the western tradition than Hollywood’s crippled efforts of the same time period (look no further than the musical that Leone’s star Clint Eastwood made a few years down the road: Paint Your Wagon). The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, shorn of nearly 20 minutes for its original American release, is surely one of the most compelling validations of the western genre’s most elemental touchstones: the quiet stoicism of men who were islands unto themselves, the necessity of according respect to that unforgiving nightmare that is the Land, and the malleable but unquestionably unbreakable divisions between good and evil.”

Clint Eastwood’s Man with No Name may have a hidden (postmodern) dishonest streak in his race against Lee Van Cleef’s “Bad” and Eli Wallach’s “Ugly” to find $200,000 worth of buried gold, but, as Henderson notes, “the scene where Eastwood covers a dying Civil War soldier with his trench coat confirms that there’s really nowhere near as much room for debating his moral alignment as there was even in the later work of John Ford.” Maybe those who saw the movie during its original release were finding the ethical clearness that was “respectable” westerns and didn’t expect Leone’s uncontrolled movie richness. Henderson noted, “The director’s uniquely impassioned and architectural Italian sensibilities turned the American Southwest—or, rather, whatever portion of Spain his producers decided would suffice—into a dreamlike terrain of bombed-out ghost towns that still invariably host cathartic shoot-outs, amphitheater-shaped graveyards that seem nearly a mile in diameter, and wide vistas that alternate with extreme close-ups without nary a medium-shot buffer in sight.”

Now we can’t forget the amazing score of Ennio Morricone that you’re never really sure are simply background music and not simply powering the action on the screen, like how Henderson puts it, “as when a Confederate P.O.W. band plays accompaniment to a prolonged beating or when desert birds seem to be whistling along to the signature fourth-inversion riff.” He sometimes sacrifices clarity for effect (as Henderson points out, “when Wallach’s motormouth inexplicably goes all tacitly Van Cleef for one compelling scene as he “shops” for a new gun), but Leone’s cinema, now fully embraced by cinephiles and fanboys alike, is practically a genre unto itself.” However, his harmony with Eastwood’s main character – and, as Henderson describes, “thereby, the cowboy mythos in toto” – as a scoundrel, conflicted nonbeliever puts him in the same sublimate level of directors who, like Ford or Huston, simply tried to live out their own legends.

If you haven’t seen this movie, why are you reading this review? Go out and watch this film, like you should do with all great films. Especially with the famous line, “When you have to shoot, shoot. Don’t talk.” This is another one of my all time favorite Westerns. I give this a high recommendation for those who are fans of Eastwood and Westerns. You will absolutely love this one, I promise. With three of the greatest actors, how could you go wrong?